A year ago, I received a call at home from my front desk manager. A middle-aged man had just been taken to the hospital by stretcher. He had crossed the foul line and taken a hard fall on the oil. Despite stickers posted on our gutter caps warning of that risk, and digital signage above every lane reiterating it, this gentleman ignored the warnings, didn't see the hazard, and paid the consequences.

Our business works hard to communicate the hidden risks in our bowling center to our guests: whether it's invisible oil patterns, dangerous ball returns, or wet and "sticky" shoes. It's in our best interest, and our guest's. If only the investment management industry was as transparent disclosing the hidden fees their clients pay. If investment managers acted with their client's best interests in mind, they'd be busy explaining a variety of fees. Generally, these fall into the following categories: transaction fees, recurring fees, or miscellaneous fees. While the sums may appear insignificant when looked at in isolation, over time, they can have a major impact on portfolio performance.

Transaction fees

Transaction costs are like slip and fall risks. People can trip in your parking lot, on your steps, going out the front door, or even over their own two feet. You can't do much about them. What you can do however, is to look for ways to minimize them.

Wall Street traders sit at their desks every day offering to buy and sell stocks, bonds, and commodities on behalf of their clients. Much of the time, sales to these clients are made from inventory sitting on the bank's books, while purchases are accommodated by committing firm capital. This is where the opaquest of expenses come in. When your bank/broker dealer sells you a security out of their inventory, they are compensated by selling that security at a slightly above market price, a difference called the markup. Alternatively, when buying a security from you, they will generally offer a below market price, or markdown. Either way, the true expense won't be known or disclosed. The markup/markdown goes to the firm for taking the risk.

Commissions, on the other hand, are clearly disclosed. You pay your broker a commission to buy or sell securities. That compensation to the financial professional, hopefully, incents them to act in your best interest.

Buying mutual funds rather than individual stocks or bonds is an alternative way for an individual to invest in the financial markets. To compensate the investment professional selling the fund to their client, some mutual funds charge a fee, a sales load charged to the buyer and then shared with the salesperson. Sometimes this compensation is paid upfront (e.g., you buy the fund for $100, pay a $5 upfront fee, which leaves you with only $95 in invested securities), and sometimes it is paid in the end, out of sales proceeds when the fund is sold (back-end load).

These transaction fees are not necessarily communicated beforehand to the investor. More likely, the investor will need to read a 50 plus page prospectus to discover for themselves what fees exist.

Recurring fees

No service provider works for free. Even if you don't see a line item charge. . . I promise. . . you're paying something for the service. When working with an investment advisor (as you know, a practice I highly recommend), clients are charged an annual fee in return for receiving professional investment advice. Typically, this fee is expressed as a percentage of the assets being managed, e.g., 1.0-2.0% per year.

Unfortunately, the fees don't end with your advisor. The funds your advisor purchases on your behalf also charge fees. Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) are one of the most efficient and inexpensive ways to invest in stocks, bonds, or commodities. But there are still incurred costs for managing those funds. The prospectus accompanying the purchase of your security will typically express these expenses as a percentage of assets, or as an expense ratio. When buying mutual funds, it gets a little more complicated. In addition to the expenses incurred investing the money, there could be other charges, like 12b-1 fees, that aren't even realized in the pursuit of performance. They are marketing expenses of the fund, passed onto investors. They serve the investor no real purpose except as a drag on performance.

Miscellaneous fees

Transaction and recurring management fees make sense intellectually. Regrettably, brokerage and mutual fund account fees don't stop there. There are myriad other ways these firms capture income. For example, they may charge a small account fee just for hosting your account on their platform. They may charge inactivity fees to accounts not transacting regularly. Trading platform fees, paper statement fees, account closing fees, and account transfer fees are other potential charges you may incur. In the case of retirement accounts such as IRA's, there is usually a custodian fee covering IRS reporting costs required on these types of accounts.

Fees matter

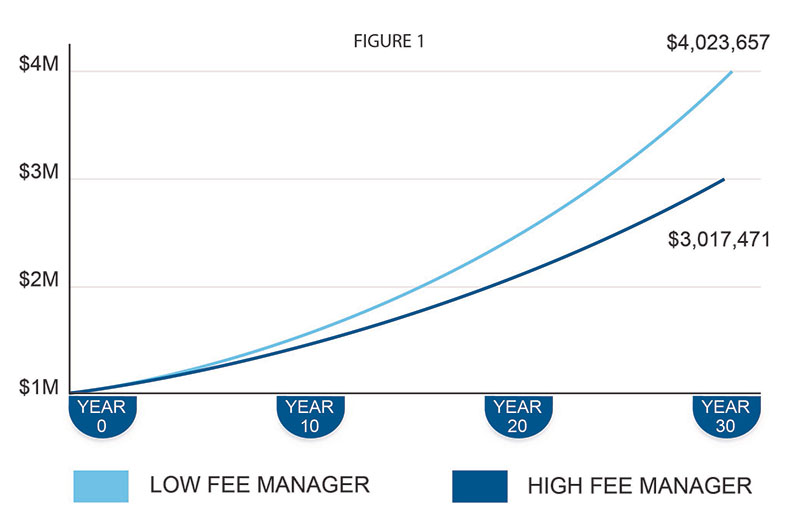

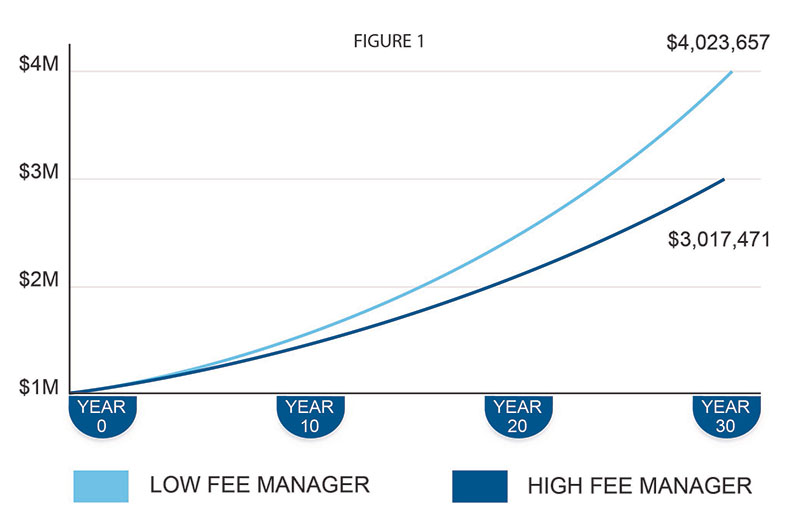

In my July 2017 article, I quantified the drag these fees have on portfolio performance. I used the following example with two identical investors, one employing an advisor using low-cost index funds (1.25% per year cost, all in), the other with an advisor utilizing high-priced, high-fee mutual funds (2.25% per year). Assuming identical 6.0% annual returns on the same $1M initial investment over a 30-year period, the low-cost strategy generated an additional $1M in returns (see Figure 1). That's money that could have been in the investor's account, your account. Instead, that money "leaked" out as fees. Like our bowler who slipped on the oil and broke his femur (I'm not kidding), uneducated investors are being hurt by invisible fees. The only difference? My bowler experienced tremendous pain while investors remain oblivious to the assault.

Now you get my point. Fees and expenses are characteristic of the investment management world, but little effort goes into communicating them. Too often they stay hidden. And what you can't see will hurt you.

Click here to view our Disclosure